A Time Full Of Life

We want to experience real human beings and real life—and yet we are often terrified by what it asks of us.

Hello dear reader,

How are you this week? Have you taken a full-body breath?

The other day, I saw a deer’s leg in the grass, still partially covered in fur near the hoof, the other side bare bone. My dog smelled it and I called her away. Let the leg be, I said, and offered love and good wishes to whoever once ran on it, when it was possible still.

My dad’s cancer has spread to his brain after rupturing through his bones, and tomorrow I am taking him to his first radiotherapy appointment. It will help for a few months, they said, and he cannot decide whether he wants to trust death or miracles more. I think we all struggle with it, in our own ways.

I have not had much to say lately. Most of attention has gone to quiet observation—holding space for the unravelling of the unknown. Watching the humanness in my father rise to the surface as the illness claims his body, while also seeing the same truth weathering my grandma’s gentle silhouette in pain. Our dog has gone blind in one eye, slowly withdrawing from this finite world into the endlessness he, himself, contains.

A conversation had happened earlier this week, bringing to a close an indescribable, beautifully loving space, held trustingly by two pairs of hands, now made separate. In this portal of a breakup, as

beautifully phrased it, I tried to do a somatic practice I was told would help me in some ways to move the stagnant energy, a buildup from lifetimes. So I slow-crying-danced in my bedroom this morning, while my dog looked at me completely confused. I then stroked my own cheeks and hands gently over and over, as he once would, as I would do to him, telling my heart it is all okay and that I’ve got this.Leaving out of love is one of the hardest, gut-wrenching decisions life tasks us with. It defies common sense, bends all the truths we were taught about life, and leaves us open to a love that remains—but cannot be cultivated as we dreamt it would.

When I hold my own hand, I trust I’m not alone doing it. Perhaps all of us holding our own hands, stroking our own faces, are, in some ways, offering that to each other also.

How vast is the heart? How much can it hold?

All of it. Yes.

These days, I am drawn to the fields. I used to prefer to walk the forest paths; now my feet long for the grass, eyes yearn for the vast and untethered spaces, bound only by the arbitrary horizon, a line drawn only in thought. The landscape stitched with coarse tufts of grass, hardened by winter, reaching toward light, like we all do. And the blue sky open above me, accessible, holding the sun—its warmth enveloping my skin more and more closely. At the edge of the forest, early trees blossom—and so do I.

Sometimes, when I walk after the rain, I brush my face underneath the soaked pine branches to receive their blessings; I let the water droplets run through my hair, down my forehead, across the lips, sink into my skin pores, watering me.

In every undoing, there is a receiving.

One can smell spring in the air. I will not attempt to describe it. Words are, anyway, only meant to sketch the form of the happening—enough to hold its shape. The word-bearer, which would be you, dear reader, now that you have received my words, is the one entrusted with tending to the fillings between the lines; the sweet weight of meaning is yours to carry, and to make your own.

This is a time full of life. Exactly how life is. In other words, life speaks to us most directly through our bare humanness.

The difficult beauty of experiencing someone else’s humanity

We often cannot help but try to make the world around us feel a little more “ours.” In relationships, we may attempt to shape our partners in ways that make them, even slightly, more like us—something we can understand. We carefully decorate our bodies and homes to reflect our characters and preferences, our online spaces designed to communicate our silent truths.

Other beings inhabiting this world with us are, as Tom van der Linden of Like Stories of Old noted, “transformed into objects to be known, or to be encapsulated within our own extended sense of self.” Life’s expressions, experienced outside ourselves, often come to be understood “predominantly in their relation to us—rather than as beings that we truly experience and appreciate in their own right.”

We often place ourselves at the centre of the universe—not merely as a pragmatic consequence of experiencing life through an individual perspective, but also as a result of philosophical traditions that assume reality is to be understood from the vantage point of the self.

Philosopher Emmanuel Levinas drew particular attention to the significance of encountering the world beyond this self-centred view, inviting us to reconsider our relationship with all that surrounds us. He spoke about encountering another person not merely in the physical sense, but in what he called the face of the Other.

This “face” was never merely referring to outward appearance. Rather, it concerned itself with something much deeper—the irreducible presence of a human being that calls us into relation and recognition.

In German, one might speak of the Gestalt, a term popular in therapy—the felt wholeness of a person beyond their visible features. Related concepts include the essence, the holistic presence, or the living entirety of a being. It is the presence of another that interrupts our self-enclosed world. Someone whose aliveness, once fully noticed and acknowledged in its magnitude, urges us toward a fundamental responsibility to honour the Other’s wholeness.

“Can love, in its unaccountable weirdness, hope to overcome a culture of individualism built on denying all our millions of kinships and dependencies?” asks Richard Powers in his essay for the Emergence Magazine.

This love-enabled encounter is what allows us to truly recognise another as a being with their own interior richness—thoughts, longings, complexities, and dignity entirely separate from our own. It is not just a matter of seeing someone; it is a way of being affected by their presence, seeing into them.

True kinship is built upon the fundamental quality of respect for the life we encounter in the Other. Through that respect, we recognise their sacred autonomy, submerged in the ethereal unity.

One might easily dismiss it as an obvious fact, for after all, we know very well that others inhabit inner lives as rich and layered as our own. And yet, to feel the fullness of someone’s existence—rather than simply acknowledge it in theory—can be unexpectedly disarming.

It unsettles something in us, precisely because it is not abstract. Its impact is not only mental—it is visceral, reverberating deep in the body.

We don’t need to love other beings to be in a position to recognise their essence. But once we recognise their essence, we might no longer be in a position to withdraw our love from them.

When we truly see others, we see into them. And to see this way is to cross a threshold. By seeing others in their own right, not as extensions of our own story, but an entire cosmos of thought, memory, desire, and dignity, we can no longer shrink their importance and inherent freedom. We must raise to honour their wholeness.

This is the sharp edge of our longing, the edge of the forest. The trees blossom beneath the open, favourless sunlit sky. It may feel safer to remain deep in the woods, tucked away from the sky, but we rarely can find flowers there, it’s too dark in the hiding. Our shared wholeness is disrupted by this paradox: We want to experience real human beings, real life in its full blossom—and yet, we are terrified by what it asks of us.

There is a certain kind of sadness in this contradiction: how we yearn for closeness, and still pull away. We hide just enough to feel safe, even as we ache to be held under the open sky of another’s love, to be known entirely and unconditionally, to be seen into everything we hold.

The more we sense the gravity of another’s presence, the more we are required to stand fully in our own. And that can be frightening. Yet, it is not our softness that endangers us, but our refusal to honour it.

Sometimes, I think our fear of pain or inconvenience is not really about hardship. It’s about the rawness of being alive without armour. We’ve been taught to fear discomfort more than disconnection. But the fear of pain is often the fear of life itself.

A time full of life isn’t always a time of grand adventures, or joy, or conventional success. Sometimes it’s the moment when we let the ache come close. When we stay with the weight instead of numbing it. When we let ourselves feel all of it—not because it’s beautiful or inspiring (although, certainly it might make for a good essay or a poem later), but because it is simply the truest, most honest state we can be in. Life speaks most directly through our bare humanness.

I was told, like many, that vulnerability is a liability—a function by which we become fodder for the ravenous mouths of the world. But I no longer believe that. Those who say it are, I think, frightened of their own tenderness—a trembling animal living within them, which they could never bear to name, let alone tame or befriend, as The Little Prince once taught us.

“We think too much and feel too little,” said Charlie Chaplin, who celebrated humanness through humour. “More than machinery, we need humanity. More than cleverness, we need kindness and gentleness.” Softness is not weakness. It is the material of conscience itself. And in a hardened world, letting others affect us is not a testament to our naïvety, but to our recognition of the last of human freedoms: the freedom to choose our attitude, as Viktor Frankl taught.

Levinas wrote that in the face of another, we glimpse the sacred, the divinity they home. “God rises to the surface of being in the face of the Other,” he said—not as theology, but as lived and felt recognition. Even if we never speak of God, we know what it is to feel reverence, a sense of something bigger than life which we encounter in moments of beauty, in the liminal spaces of life’s unfoldings—and in each other. It is something we might be unable to name, but instinctively feel.

That, in turn, would also explain why hurting someone becomes such a profound violation, an existential wound. It is not only a moral transgression, a crime against humanity but a spiritual fracture—a wrongdoing towards God.

When we harm another being, there is a deeper wisdom within us that knows the magnitude of this act. A tightening in the chest, and a deep—unbearable at times—unease that seems to remind us we touched something sacred, but without due reverence and respect. Guilt is not only an ethical concept but a natural bodily response. A biological architecture that reminds us, in the most ordinary ways, that we belong to each other.

In other words: what the experience of guilt could imply is that we are biologically incentivised not to hurt each other.

The light in the eyes of others, they guide you on your way

“We all want to help one another, human beings are like that,” pointed out Chaplin. “We want to live by each other’s happiness, not by each other’s misery.”

Still, we find ways to circumvent that deep knowing. History, again and again, has shown that cruelty does not begin with rage. It begins with erasure—with the gradual stripping away of another’s humanness. When we no longer see someone as whole, we lose the internal resistance that would otherwise stop us from harming them.

We see this not only in the devastation of war or injustice, but in smaller violences too—in how we reduce others to categories, roles, ideologies: the bus driver, the waiter, the boss, the spouse, the child, the immigrant, the beggar, the inconvenience.

Labelling the Other, we narrow the richness of their existence. We render them knowable, manageable—and in doing so, we lose sight of what cannot be contained in a label: their complexity, their longing, their light.

And perhaps the most haunting truth is that when we dehumanise others, we begin to lose our own humanity as well.

We shrink into the roles we’ve been given, performing the version of ourselves that feels acceptable and manageable to others. Slowly, the richness of our own inner life, too, begins to fade. The body grows heavy. The world feels farther away—not because it changed, but because we stopped meeting it fully, we abandoned our own wholeness. “Though the sensation is often experienced as one of numbness, our body is essentially screaming at us—imploring us to come back, to get back in touch,” Tom van der Linden reminds us.

As Levinas suggested, the numbness we experience may trace back to something deeper—a worldview shaped around the self as centre, a perspective earlier reflected in how we tend to see others not in their own right, but through the lens of our own needs and projections.

But the face of the Other disrupts that. It reminds us we are not the centre—just one being among many, all equally complex, equally robust and throbbing with life. To truly see someone is to let that truth undo and reorder us. To let their full presence interrupt our self-made order as a call back to a deeper belonging.

It can be uncomfortable to let someone’s reality pierce ours—to realise how inattentive we’ve been, how little we’ve listened. But it’s also the moment we return to ourselves, enabling life to regain weight and shape.

By encountering another’s humanity—in all its messiness, ache, and light—we confront our own unseen, murky territories: the shadowlands of entanglements and avoidances. This confrontation is also an invitation to come alive again—fully. It is a chance to remember what it feels like to care with the whole of our being.

The work that we are called to, then, is one which enables us to rejoin human to humility to humus, through their shared root. (That root is dhghem—an ancient Proto-Indo-European word meaning earth, from which all three words originate.)

“Kinship is the recognition of shared fate and intersecting purposes. It is the discovery that the more I give to you, the more I have,” writes Richard Powers. We meet the Other in their wholeness not because they matter to us personally, nor because they support a broader purpose that loops back to serve us—but because we truly see them as human beings. And deep down, we know that is enough.

Sometimes I wonder what kind of world we would build if this were our compass—not profit, efficiency, convenience, image, not even certainty, but the weight of our shared humanness.

How would we speak, work, build communities, if the weight of another’s humanity were not something we feared and resisted as an inconvenience, but something regarded as rightfully sacred—something we trusted to guide our choices?

It may overwhelm us at times, and perhaps it should. Maybe the ache we feel when we truly see someone—and in them, mirrored our own imperfectly full existence—is the very thing meant to guide us home. We have spent so much energy trying to become untouchable—but what if it’s our capacity to be touched that matters most?

Let it be love, not fear, that leads us. Let us be guided by the light in the eyes of the Other.

A little announcement

Dear readers,

My offering here will take on a slightly different form.

So far, I have been publishing an essay each week. I will continue doing so, but in one week of each month, instead of an essay, I will share with you a piece of my poetry. I hope it will bring a new texture to your experience here — a different way of engaging with thought and feeling.

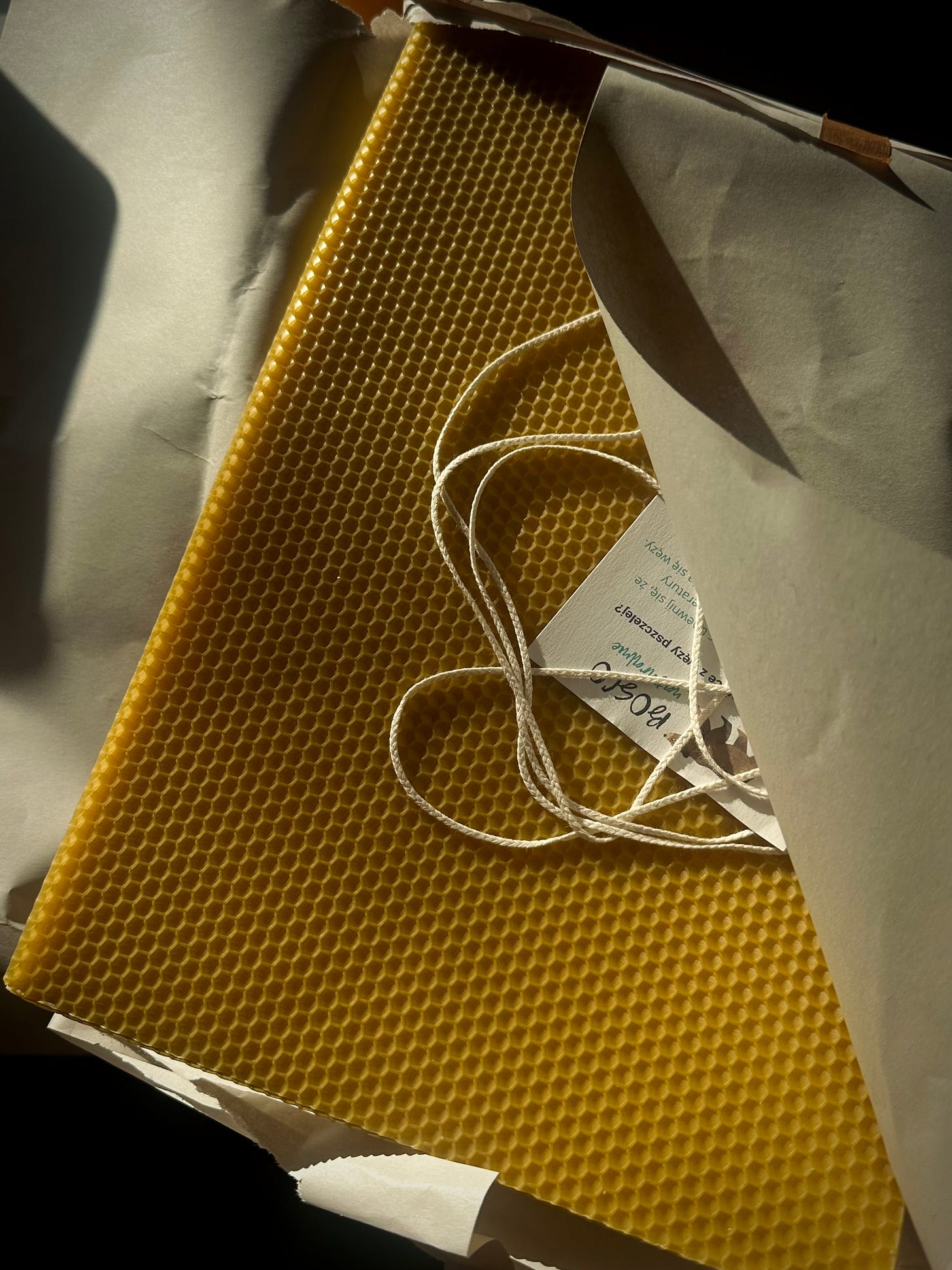

Additionally, to honour the generosity of those of you who choose to financially support Stacking Stones and my practice of offering through writing, I am considering sharing a new kind of writing each month — one in which I offer insights into my process of writing, meaning-making, finding one’s own voice, using mindfulness in the craft, and so on. I would love to hear your thoughts — would you be interested in such an offering? Would it benefit you? Please do let me know, either in the comments below or in a private message :)

If you find warmth, comfort, inspiration, joy, motivation, or anything else of value in these letters and would like to show your support, please consider becoming a deeply valued patron by upgrading to a monthly or yearly subscription. This will also give you access to the full archive. If you have a financial restriction, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

A couple of questions to you, dear reader:

What might change if we let the light in the eyes of others guide us more often?

Where does reverence live in your life, waiting to be met with your attention?

What are the small gestures of light you are tending to these days—and in them, how do you return to the sacredness of being human?

I am speechless at the beauty of your writing. I suppose there is light in the way I care for my plant, love my daughters, and go out of my way to help others. Recognizing connection as sacred is the first step toward a kinder community you described. Second, willingness to be open to it. And lastly, being intentional about it.

Rawness. The seed cracks past the surface ignited by an inner fire, to be seen, at last. Beauty.

Courage is meager in face of this.

This is real. I am moved, shaken, touched, sparked and cracked open. I am a witness to your ripped, glowing, full, light, deep healing heart. Your being is admirable - or rather, I admire your being.

I saw my self in these words, I heard my self through these words, I felt my self in these words. This reflected a part of mine I sense others respond to, yet, I never could hold awareness of for my self. Thank you. Immeasurable it is how this piece is.

Heal, be. Be.