Hello dear reader,

How are you, truly, this week? How do you hold yourself through transitions?

This is Part One of the new, two-week series From the Archive (April 2025), revised and this time narrated. You can choose to read or listen—or do both!

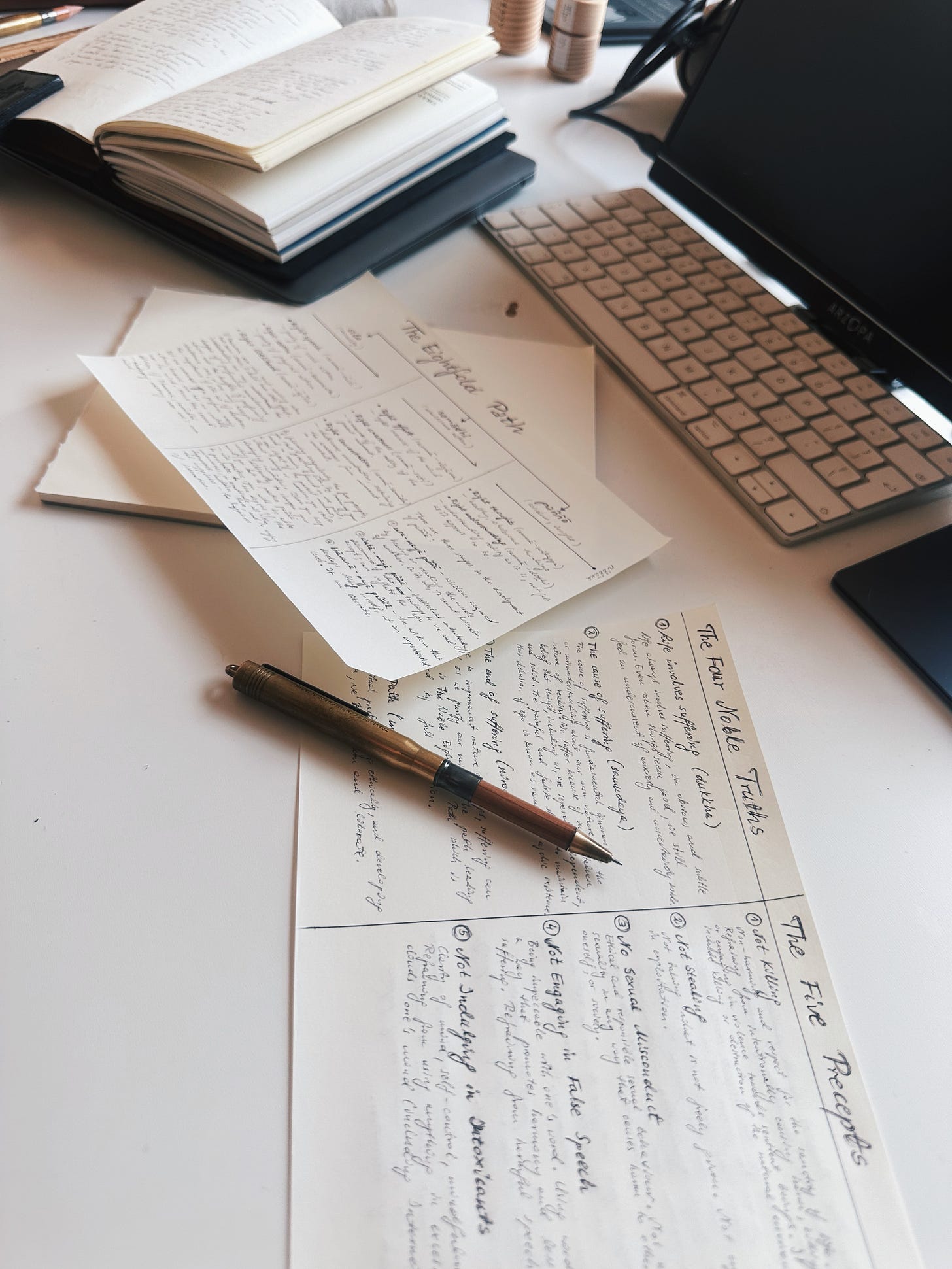

I’m resurfacing this now because many of you asked for an easier read of my longer letters and it still feels timely. I’ve also received positive comments on the previous series I’ve published, so I thought I’d offer you a new multi-story experience as we enter a new season. This letter was originally written at the cusp of season change as well, and it holds both the delicacy as well as the mystery of transition at its black-inked heart.

Transitions are a good time to re-establish routines and create structures in our lives that hold us as we move through the uncertainty of change; as we open ourselves, over and over again, to the flow of the necessary undoing and restoration.

With this series, I offer you one of such containers for the coming weeks—and I invite you to think of what routines of kindness towards yourself (or gentle rituals) you would like to strengthen or introduce fresh into your day-to-day throughout November.

And if you are in an explorative-reading mood, here are Part One, Two and Three of the previous series on deepening the sense of belonging, awakening to more joy, and the gifts of letting go.

I hope you find a sense of smile and value in reading this, as we make this walk together 🤍

Squatting on the forest floor with my hands pressed to the murmuring earth, slowly letting myself remember that I am held, I noticed a tree with one of its large branches hanging half-broken. A tree I visited again last week, bathing my sight in the wondrous richness of Autumn’s adornment.

Seeing it for the first time, I realised I did not think of it poorly because of its seeming impairments. It was an obvious fact that it is no less perfect a tree, even with one of its branches limp. I simply accepted it as it was, no less or more beautiful than other unbroken trees.

And when I later approached that tree to hug it, as I often do with those who have seen much, and remained—and especially when it has been a while since I experienced a warm human embrace—I began crying.

Holding its trunk, I realised that this tree accepts me the same way I accepted it just a moment ago. With some of my branches limp, dangling half-broken around my body helplessly, others still reaching to the sky, risking hope—I am no less perfect a human.

Standing there, my soft body pressed to the wooden one, I felt unbound love that subjects itself to no condition infusing me as if through osmosis, and for the first time in a long while, I felt welcomed just as I am.

When, with my hands pressed to the soil still, my body lowered and compressed, I realised I was experiencing the forest from the vantage point of a fox, a baby deer, or an adult one perhaps—its head half-lifted mid-graze, eyes sharp, ears attentive.

I noticed spiderwebs shimmering in the late afternoon sun; I heard birds chirping and singing in the canopy. I thought of the wealth of ants and beetles and worms underneath my palms; the mice, squirrels, deer, boars, foxes—all silently sharing that moment with me, possibly observing me from somewhere.

I felt that even if we do not know each other, we could be friends. We are friends. I thought of all the animals inside my body—the bacteria and microscopic kin, creating entire ecosystems that power me to life. All sharing this breath together with me.

And in that moment, gratitude filled me in recognition of this excellent company. Subtle communion, belonging without needing to be seen. Suddenly, I did not feel as alone. This place has lent me its wisdom about understanding who we are to each other and how we are to each other. And how I can be to myself.

The spiritual path is a paradoxical one. On one hand, it brings us to places of belonging we may never have known, because for the first time perhaps we are discovering them deep and unshakeable within ourselves, rather than in the outside world. On the other, we might find that we have never before felt more isolated, different, unfitting, or straight-up “weird”.

More and more, what I experience is not something I can openly share with others without making myself sound like an oddity—or someone whose mind went running wild in the fields, untethered by the constraints of “sanity”.

There is humour in it, but also a certain dose of sadness. I have moved through the mountains of grief for what I am leaving behind. Freedom always comes at a cost.

If you have been feeling similarly, you also probably know that despite all this hardship, you would not trade where you are now even for a day of the once-present sense of “belonging”. Because you know all too well now, as I do too, that it was just illusory—a mere stretch of conditioning you were yet to let go of and strip away, layer by layer.

As I kept wandering through the forest, losing my mind and finding my soul, as is popularly attributed to John Muir, I stumbled upon a mossy tree stump. On it, I found three blue-striped feathers, and a few steps further, a grey and fluffy one. “Gifts,” I thought, and put them in a front pocket of my jacket. I felt blessed and spoiled.

“Why disregard the present?” I asked myself, recalling the words once offered to me by a dear voice. “Why, even though the future holds its overwhelming and constant proposals of transformation, the now has already declared such great blessings?”

When I got back home, I bathed the feathers in soap and warm water, and put them on the windowsill to dry in the setting sun. The next day, I brushed them carefully and placed them on my small shrine to be reminded: empty hands mean that I am finally ready to receive. The impulse to grasp is precisely what evokes the feeling of lack.

As a little girl, I used to make wavy motions with my arms whenever I was running down the staircase. I do not know why; I was not thinking or imagining anything in particular while at it. It simply felt… fitting. I would do it every single time. Until I did not anymore, of course—as it appeared to me unserious. And as most of us have been told, to finally grow up, one needs to serious-up.

“We are raised in cultures that really narrow down the parameter of how much we get to inhabit of our own life,” points out Francis Weller, a psychotherapist, writer, and soul activist. This narrowed-down parameter is devoid of the freedom of expression, joy, and playfulness which we still embody in the early years of our lives, but soon enough abandon as we pass the threshold of adulthood, laced with a profound sense of inadequacy.

But it is not only joy and a sense of whimsy we are denied when dwelling in an adult body. It is also no longer acceptable to feel and express sorrow fully when it washes up against our jagged shores.

Even before we collect our first ID, we are already entrenched in the stickiness of performative adulthood. It is not maturation. Some of us never truly grow up—which is to say, some of us never truly blossom. Instead, we hold these wild, beautifully honest parts of ourselves with judgment and shame.

I did it again last week, near the forest—the waves, I mean. I was making my way down a hill in little jumps and my arms just flew up and assumed the wavy motion. It felt fitting, as I said. A reclaiming of being before it was curated. “If someone saw me now,” I thought, “they would think ‘God, she’s a freak’”—and I laughed at it with delight.

Freak, after all, did not always carry the weight of shame and exclusion it does today. It once spoke of brisk movement—sudden gestures, dancing without apology. Another early meaning was tied to change itself: whims, caprices, shifts that made no rational sense but resonated deeply. A “freak of nature,” for example, once described something unexplainable—often natural or divine.

Before it was used to mark people as strange or deviant, it belonged to the language of fluidity—of letting one’s being shift shape, unravel, express, and re-form again.

At last! At last I let myself be just the freaky way I am. The truth is, if we all welcomed back all parts of ourselves and wore them without shame, we would all be the most lovely “freaks”—and in such an openly diverse universe, nobody would be shamed for being one.

“When you do not follow your nature,” Dane Rudhyar pointed out, “there is a hole in the universe where you were supposed to be.” Until we mend all the holes, however, embracing our entire, freaky selves—especially among the few who do—is not always a light or joyful experience. And yet, it is one worth everything.

For when we follow our nature, even if we do not know each other, we are already friends.

If you find warmth, comfort, inspiration, joy, motivation, or anything else of value in these letters and would like to show your support, please consider becoming a deeply valued patron by upgrading to a monthly or yearly subscription. This will also give you access to the special, paid-only letters. If you have a financial restriction, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Before you go

Questions to aid you in this week’s reflection:

How can you widen the parameter of how much you get to inhabit your own life?

What part of your so-called “freaky self” is quietly asking to be stepped into without shame or restraint?